Last week the Pulitzer Prize committee issued a posthumous her citation to renown journalist and antilynching activist, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, 89 years after her death. Over the course of her life, Wells-Barnett was unrelenting in her mission to tell the truth about lynching in America during a deadly era in which whites, sometimes in small groups, sometimes in large groups, committed often brutal and torturous extralegal murders of Black people, most frequently Black men. Over the course of a nearly a century, between the 1870s and the 1950s, more than 4,000 lynchings were recorded in the United States. In their defense, white men routinely claimed that these spectacles of public murder were necessary to keep Black men—dangerous, criminal, and rapacious—in line and, most importantly, to protect vulnerable white women.

Wells-Barnett’s first book, Southern Horrors, published in 1892, resulted from her investigations into these claims. Her findings often disproved the public claims made my whites. Instead Well-Barnett documented that Black men were killed for all manner of petty slights or violations of the de facto racial code of the region. Black men were lynched for being economically successful, or thinking too much of themselves. Sometimes they were killed when their consensual sexual relationships with white women were discovered, and their paramours alleged that they were raped in order to preserve their reputation. “It is a contribution to the truth,” Wells wrote in the preface to her work, “an array of facts, the perusal of which it is hoped will stimulate this great American Republic to demand that justice be done though the heavens fall.”

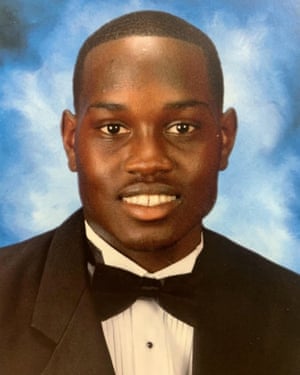

The news of Wells-Barnett’s award came on the heels of an increasing number reports of the murder of a Black man, Ahmaud Arbery, in Brunswick, Georgia. He had been jogging when two white men, Gregory and Travis McMichael, father and son, ordered him to stop. When he did not, and resisted the efforts of these strangers to accost him, they shot and killed him. The McMichaels were aided by one other person, who recorded the shooting. Their intention, they claim, was to make a citizen’s arrest. Arbery fit the description, they said, although there had not been a burglary reported in the community for six weeks. The version of events offered by the McMichaels, however, was accepted whole cloth by district attorney George Barnhill, aided by the elder McMichael’s long career in the legal community as a former officer, the many cozy relationships with the gatekeepers who could decide to charge him or to free him, and the old habit of assuming the criminality of any Black man. Arbery’s family was told that he was killed after he attempted to rob a home. Not until many weeks later would they learn something closer to the truth.

That their son, Ahmaud Arbery, had been lynched on February 23, 2020.

Arbery’s extralegal murder is only the latest incident, fueled by a pair of centuries-old phenomena: the white obsession with the control and the commodification of Black bodies. These ideas were fundamental to the practice of chattel slavery in the United States, and were codified into the nation’s constitution. Even after emancipation in 1865, these ideas motivated the creation of systems that facilitated legalized segregation, voter disenfranchisement, peonage, and convict labor. These ideas, along with the concomitant devaluation of Black life, fueled lynching. If it could not be controlled or profited from, the uncontrollable Black body was declared criminal and thus eligible for destruction.

These are the foundational elements of the sociopsychological balm of whiteness, the glue that has pulled together, and continues to unite, people with white skin, no matter their nationality or ethnicity: the power invested in whiteness vis-à-vis the subjugation of people whose African ancestry is expressed phenotypically. It is the reason that poor white men took pride as members of the slave patrols in their ability to police the Black property of their betters. They may not have possessed wealth but they could exercise power over someone, at least. Whiteness, in this way, became authority, especially over Black people. It is the reason, just this past week, that a group of armed vigilantes, led by an off-duty deputy sheriff, felt they could confront, threaten, and illegally attempt to search the home of a Black family in Port City, South Carolina. It is the reason that the McMichaels’ claimed, and the district attorney accepted, Ahmaud Arbery had to be shot: he did not stop when commanded by a white man, whose only visible authority was his white skin and his gun. This was a suitable defense. The leaders in the legal community in Glynn County closed ranks around it. It is the reason that their friend and attorney, Alan Tucker released the video of the incident. Certainly, in his legal opinion, the world would see that the non-compliant Black man caused the loss of his own life because he refused to stop within seconds of being commanded by two white men he did not know.

It was only when the snowballing outrage of the Black community moved out of Georgia and across the nation, and enough people of all backgrounds began to question the matter, that the wheels of justice were at last finally forced into motion.

When the U.S. House of Representatives passed its own antilynching bill this past February, following similar action by the U.S. Senate, it seemed like much too little, much too late. It appears now that, if the bills are ever reconciled and signed into law by President Donald Trump, it might be—sadly, terribly—right on time. At least for Ahmaud Arbery.